I am interested in ancient theories of creativity. I study the many Greek and Roman answers to the question of how things come into being, in both literary creation and biological (pro)creation. This guiding question takes me across various corners of ancient thought, from literary theory to materialist philosophy to biology, as well as their reception (for example in Neo-Latin poetry).

One the one hand, talk about creativity is now ubiquitous. The term is so widely applied that it risks losing its meaning. It does no longer only describe the lofty pursuits of genius artists but has evolved into an almost universal imperative. Everyone wants to be, even has to be “creative.” On the other hand, the concept of human creativity is now facing profound challenges, especially with the rise of artificial intelligence. In an attempt to tackle both of these issues, my research across multiple projects strives to uncover a more integrated perspective found in ancient thought.

Creativity

My first book project is titled Rome and the Crises of Creativity.

In a world where the idea of creativity as a uniquely human endeavor is not just challenged by studies of animals, but by the much more momentous emergence of artificial intelligence, a reevaluation of our ideas around creativity seems warranted.

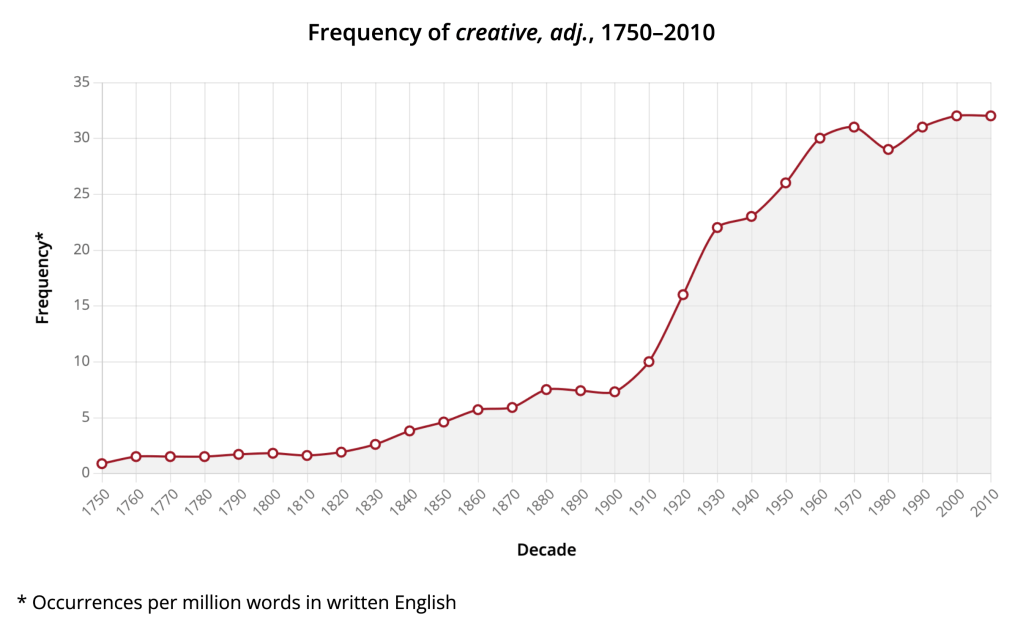

Yet the term “creativity” is not all that old:

Statistic by Oxford English Dictionary

When it gained currency around the turn of the 19th century, it often did so specifically on the assumption that such a quality does not exist in Latin poetry. Modern Western ideas of creativity were shaped in part through a dismissive view of Roman culture. Long seen as derivative and unoriginal, Rome was cast as the antithesis of a supposedly authentic Greek creativity—a perception reinforced by Romanticism and inherited by later literary theory. This project reexamines that narrative by exploring how Roman thinkers themselves conceptualized the creative act.

Though they did not have the modern term, Roman writers were heavily invested in explorations of the nature of creativity. From the get-go their poetry is characterized by an acute feeling of crisis and a compulsion to justify its own existence. Endlessly aware of their own belatedness, Roman writers felt forced to think about novel ways to explain themselves.

At the heart of the study is a historical tension between two dominant models of creativity: one to be called “synthetic,” emphasizing the recombination of existing elements; the other “organic,” drawing on metaphors of birth, growth, and embodied development. While Roman literature has often been reduced to a paradigm of the synthetic model, this dissertation advances a different perspective, one bridging these opposing models into a cohesive understanding of creativity. It does so through close readings of the Roman poets Vergil, Ovid, and Manilius, the Epicurean philosopher and poet Philodemus, as well as surrounding ancient literary and rhetorical theory, materialist philosophy, biology and medicine.

The Romans had a quite holistic approach to creativity that is very much integrated in their general view of how the world functions. During my research, I have therefore realized how this first project becomes increasingly entangled with my second:

Ancient Genetics

After I waved goodbye to biology proper after my bachelor’s degree, I came to it again from the perspective of history of science.

For a few years now, I am teaching classes on what I call “Ancient Genetics,” exploring the long history of reproductive biology. Where does life come from? Why do we look like our parents (or not)? And what is the effect on their societies when people start to pursue such questions more deliberately?

The more I get into it, the more this research starts to overlap with my work on “creativity” more generally. In the pre-disciplinary world of antiquity, drawing hard lines between different areas of scientific inquiry made much less sense than today.

I often turn to cases where ancient thought on biology, medicine, and literary production overlap. In a forthcoming study, for example, I look at how writers and doctors often appear in the same narratives (so much so, that the famous doctor Celsus can go as far as starting his large encyclopedia on medicine with the observation that we only started to need medicine in the first place when people started writing!).

Further down the line, I am hoping to turn all the things I learned over the past years into a student-focused text book.